Money

How the governing structure of the proposed PGA Tour-Saudi deal hints at who will have the real power

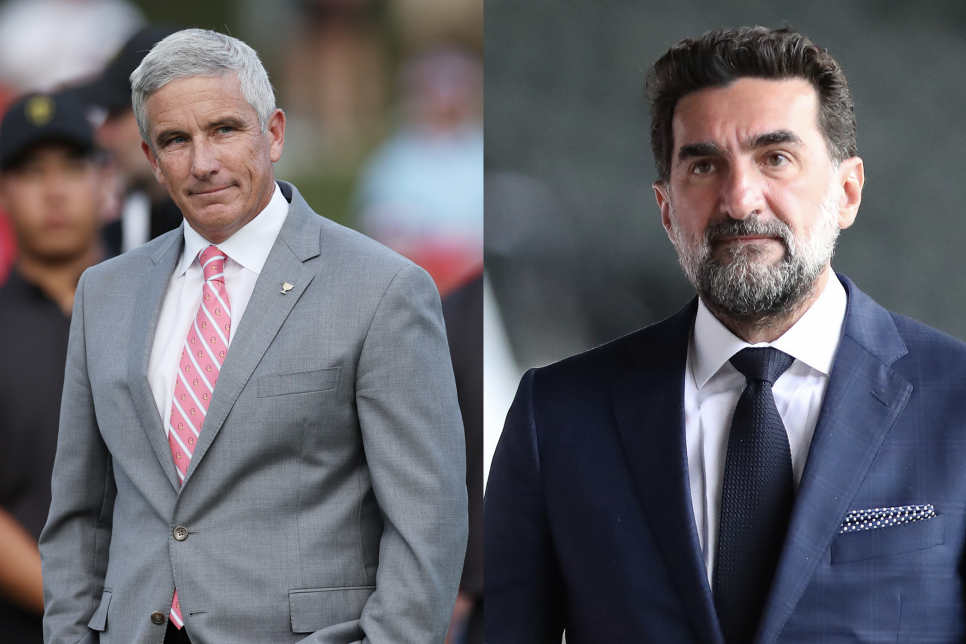

PGA Tour commissioner Jay Monahan (left) will be CEO of the new entity that will combine the PGA, DP World and LIV tours under one banner, and Yasir Al-Rumayyan, governor of the Saudi Public Investment Fund, will be chairman.

The announced framework of the new entity that will combine the PGA, DP World and LIV tours under one banner is short on specifics, but what has been announced—the governing structure, board makeup and future investment protocol—is enough to reveal potential clues about who will have the power.

At first read, the PGA Tour has seemingly protected its prized nonprofit status along with its control over between-the-ropes action in its events, and is assured a majority of seats on the board of the umbrella organization to go with PGA Tour commissioner Jay Monahan’s CEO title. But to one entrepreneur and corporate board member who is a veteran of multiple mergers, sales and acquisitions, the language about the Saudi Public Investment Fund’s (PIF) priority financial position makes it pretty clear who would be behind the wheel if this deal goes through.

“Does the PGA Tour think it won because it is effectively a monopoly and will now be backed by unlimited money? Maybe,” says Bruce Welty, who has started, led and sold multiple logistics and robotics companies that have a combined market value of more than $2.5 billion. “But money always wins. If the Saudis can block other investments and continue to buy unlimited shares, they basically have pre-emptive rights. They’re business people. It’s hard to imagine a scenario where they would give basically unlimited funds and not put themselves in a position where they can take control of their investment.”

Welty pointed to the PIF’s acquisition of Premier League soccer club Newcastle United in 2020 as a bellwether for the PGA Tour partnership. In 2019, the PIF was reportedly offered a minority stake in Manchester United for $800 million. They declined and ultimately bought a controlling interest in Newcastle for $300 million. They've invested $200 million to retire debt and upgrade the roster, with an eye on competing both on the field and in terms of valuation with Manchester United, which is reportedly featuring a $6 billion price tag for its ongoing sale.

Even if the PGA Tour-Saudi deal language stipulates a particular specific executive board makeup, if those terms aren't durable or permanent, they're ultimately subject to change. "In business, control shifts within a company. When the board makeup changes—like when new members join—the board can make decisions that are completely contradictory to the original charter,” Welty says. “In this case, how firm are the commitments? If they aren’t, it doesn’t matter what anybody says today. They can do whatever they want down the road.”

All of that assumes one basic fact Welty does not consider a foregone conclusion: That the deal goes through. Indeed, in the days since the surprise announcement, the question of whether such a deal would pass government scrutiny, either from Congress or the Department of Justice, has become a popular topic of discussion. The lack of specifics on what the new entity might actually look like makes it hard to know its true viability, but Welty is among those who see potential issues.

“Everyone has a take, but the general universal take I’ve heard is that it smells bad. Maybe the PGA Tour feels threatened, and this is the best they can do to preserve their franchise. But going from being a not-for-profit to a for-profit, that changes everything. If you’re a for-profit business that has a monopoly? It’s impossible to think that that won’t be the subject of a lot of scrutiny,” Welty says. “Mergers and partnerships happen all the time. It’s part of the game. You’re competitors until you aren’t. Generally speaking, there's usually a reason for a merger to happen. Usually, one of the companies isn’t doing so well and needs to merge. It doesn’t typically work when it's a merger of equals. It's also clear because there’s a profit motive at the end of the day. The deal gets done to increase shareholder value. With this, the motives aren't entirely clear. Is this to avoid a lawsuit? What are the Saudis’ motives? What are the incentives of the PGA Tour leaders? We don’t know.”